Reformers push changes following disorder in Pennsylvania’s court

It didn’t go viral on Twitter or inspire a Saturday Night Live spoof, but the Supreme Court candidate debate in Harrisburg on Oct. 14 was arguably as important to the citizens of Pennsylvania as the presidential debates.

At the debate, the three Democrats, three Republicans and one independent running for three vacancies on the Pennsylvania Supreme Court offered their credentials and the reasons people should vote for them.

Or, perhaps, reasons that they should not even be voting on judges. “I’ve never let politics enter into my process,” said a Republican candidate, Anne Covey. She prefaced that statement with this one: “I’ve always served with honesty and dignity; I’ve always decided matters impartially.”

“It’s something I think everybody in Pennsylvania is tired of and we’ve got to get out of this mess that we’re in,” said Michael George, another Republican candidate.

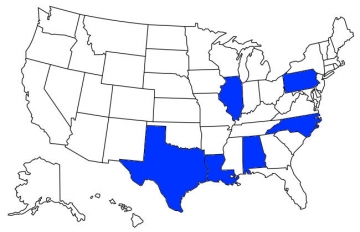

Pennsylvania just one of six states to elect appellate jurists. Alabama, Illinois, Louisiana, North Carolina and Texas are the only states other than Pennsylvania that choose all appellate judges in partisan elections.

Pennsylvania just one of six states to elect appellate jurists. Alabama, Illinois, Louisiana, North Carolina and Texas are the only states other than Pennsylvania that choose all appellate judges in partisan elections.Although Covey and George lost in the Nov. 3 election, their remarks seemed to touch on an issue that judicial reformers in Pennsylvania have been bringing up for decades: Why does Pennsylvania, like only five other states, continue to elect appellate judges in an election in which candidates run with party labels?

The question took on added significance in this year’s election, because two of the three vacancies on the Supreme Court resulted from scandal. One justice was convicted of using state workers for political purposes, and another resigned after being caught in a pornographic email ring.

Critics of electing appellate judges want a system in which the governor nominates judges to the courts, and the state Senate confirms those nominees. That resembles the system used in the federal government – the president nominates, and the Senate confirms.

On the state level, such a system usually provides for a nominating panel to suggest candidates to the governor. Another common feature is a retention election after a certain length of time, in which the voters decide whether an incumbent judge should continue to serve.

Those who favor this system, which they call “merit selection,” say it would produce judges of higher caliber. They say it would end the common practice of lawyers donating to judicial candidates, who, if elected, might rule on cases in which those lawyers represent clients.

Opponents of an appointment system say it would not remove politics from the process. They contend that appointed judges tend to fall in line with the ideology of the executive who appointed them.

Furthermore, the opponents say, politics would still affect the composition of the court. Florida, a state that uses merit selection with votes to retain judges, saw the influence of campaign spending in its 2012 election. The Koch brothers Charles and David, industrialists who are nationally known for spending money to shape political opinion, funded a conservative political advocacy group, Americans for Prosperity, which aired ads criticizing the three justices up for retention.

The ads failed; all three retained their seats on the state’s Supreme Court.

Vanderbilt law professor Brian T. Fitzpatrick – a critic of merit selection and supporter of gubernatorial appointment – says his research shows that merit selection tends to produce more left-leaning judges.

“The lawyers of a given state are not representative of the people of the state,” said Fitzpatrick. “Lawyers are more liberal. The evidence has only gotten more damning.”

Fitzpatrick points to his own research, as well as to a recent study by Monica Sen and Adam Bonica, assistant professors at Stanford and Harvard Law, respectively. Their findings show that lawyers are increasingly more liberal than the general populace, while judges are more conservative.

In 2000, the Tennessee Supreme Court declared that women have the right to abortion under the state’s constitution. Fitzpatrick singles this case out as a perfect example of merit selection states having Supreme Court rulings that fall out of line with the population’s beliefs.

Fitzpatrick also noted that merit selection takes the process out of the hands of voters. And he points out that most states’ judicial nominating structures include lawyers on the selection committees. Even when the selection committees are composed of lawyers and common citizens, Fitzpatrick said that scholars have found that citizens tend to defer to the lawyers.

While merit selection supporters argue that appointing judges would take politics out of the system, Fitzpatrick doesn’t see it that way. “I see it as differently politicized,” Fitzpatrick said.

Merit selection eliminates campaigning, he said, but it still creates an appearance of bias in that lawyers are picking a list of judges who they may ultimately appear before in court.

In Pennsylvania, elections for judges are now held every other year. Judges are elected for 10-year terms. Upon completion of a judge’s first term, he or she runs for retention in an election in which voters make a simple yes-or-no choice.

Only once in Pennsylvania has a sitting justice lost a retention election. In 2005, Russell Nigro failed to win retention after he was among members of the Supreme Court who upheld a controversial legislative-passed salary increase for members of all three branches of state government.

The plan for merit selection appears simple, but the process for changing the system is not.

For the first time in 25 years, Pennsylvania’s state legislature is moving on a bill to appoint judges. The bill would create a 13-member panel to create a list of potential judges, the governor would appoint candidates from the list, and confirmation would require two- thirds of the Senate.

If the legislation wins approval, an identical bill will have to be approved during the next two-year session of the state legislature. Then Pennsylvanians would vote in a referendum on whether to add the amendment to the state constitution.

Suzanne Almeida, program director for Pennsylvanians for Modern Courts, said the primary election in May 2018 is the most realistic opportunity for the referendum.

“Court reform tends not to be number one on anyone’s agenda,” said Almeida. Yet she thinks the timing may be right: “With all of the very public scandals, and the record-breaking fundraising and negative ads drawing attention, we’re kind of in the perfect storm.”

During October’s debate in Harrisburg, all seven candidates insisted that politics never affects a court decision. In fact, for a debate, there wasn’t much debating. Adhering to tradition and ethical canons, candidates refrained from making promises or discussing policies beyond administering the law.

The three vacancies filled in this year’s election were the most openings in Pennsylvania since 1704, when the British crown – not the public – selected justices.

One of the three openings stemmed from the retirement of Chief Justice Ron Castille in the spring of 2014. The other openings built a fire beneath the arguments of the merit-selection proponents.

On Feb. 21, 2013, Justice Joan Orie Melvin was convicted of three counts of felony theft of services and one felony count of conspiracy to commit theft of services for improperly using state workers for campaign purposes. Melvin was sentenced to three years’ house arrest and two years’ probation.

Justice Seamus McCaffery retired in October 2014 shortly after being suspended for his involvement in a pornographic email scandal, which also claimed the jobs of several top aides to former Gov. Tom Corbett. Hundreds of pornographic photos and videos were exchanged during Corbett’s tenure as attorney general prior to his election as governor. The emails were discovered by Attorney General Kathleen Kane, who was conducting an internal review of Corbett’s investigation in the Jerry Sandusky sex abuse case.

At the debate, George, a Republican from Adams County, recommended automatic recusal for justices who have received donations from anyone involved in cases that the Supreme Court hears. George shared an anecdote about a voter who approached him after a campaign event. “I really don’t want politicians on the court,” George quoted the voter. “I want judges.”

Proponents of merit selection, such as Almeida, contend that elections of judges create – at the very least – an appearance of bias.

Pennsylvanians for Modern Courts has been pushing for merit selection since 1988.

“We often elect very qualified justices,” Almeida said. “The vast majority of them are qualified. The problem of electing justices is not the result; it’s the perception. They have to campaign, they have to raise money. They’re raising money from the people who have a vested interest. The public views that as justice being for sale. It looks that way.”

The American Judicature Society analyzed the 82 civil cases decided by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in 2008-09. Of those cases, 60 percent involved an attorney or law firm that contributed to the election campaign of at least one justice. In nearly a third of the cases, an attorney or law firm involved had donated to most of the Supreme Court justices.

In 2009’s Supreme Court election – the one that placed Joan Orie Melvin on the bench – the two candidates raised $4.7 million. In this year’s race, the seven candidates set a national record by raising a total of $15.8 million reported by the morning of the election. Democrats, who captured all three court positions in this year’s election, raised nearly three times what the Republicans raised.

The record-breaking figure will inevitably be higher once all campaign filings have been tallied. The previous record for a state judicial election, $15.4 million, was set in 2004 in Indiana, a state that now uses gubernatorial appointment to choose state Supreme Court justices.

Much of the money raised pours in from special-interest groups. After the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2010 ruling in the Citizens United case, politically involved nonprofit organizations can receive unlimited funding from donors whose identity they are not required to disclose.

According to Justice at Stake and the Brennan Center for Justice, in the 2013-2014 election cycle the state Supreme Court candidates whose campaigns spent the most money won over 90 percent of the seats across the country.

In Pennsylvania, a Republican committee created a website to expose the Democratic candidates’ special-interest contributors.

According to campaign finance filings, labor unions gave $1.7 million to Democratic candidates.

Notably, Kevin M. Dougherty, who got the most votes, received $250,000 from an electrical workers union run by his brother John. Lawyers contributed $2.1 million to the three Democrats. In contrast, lawyers gave only $150,000 to the Republicans. Anti-abortion and gun- rights groups contributed heavily to Republican candidates.

Special-interest groups ramped up negative advertising. In this year’s first attack ad for the Supreme Court election, a nonprofit named Pennsylvanians for Judicial Reform said Ann Covey lied about writing certain legal articles. In response to the ad, Covey has hired a libel lawyer.

For the Pennsylvania Supreme Court elections, the Koch brothers donated $1 million to Republican politically involved nonprofits. Their donation fulfilled a prediction made months earlier by David N. Wecht, a Democratic candidate and an eventual winner. Wecht said at an April candidate debate: “The Koch brothers are coming.”

The Koch brothers’ money went to the Republican State Leadership Committee, which ran television attack ads aimed at Dougherty. An ad said that, as a Philadelphia Common Pleas judge, Dougherty placed a 10-year-old girl in the custody of a convicted murderer who subsequently beat and tortured her.

“When Philadelphia Judge Kevin Dougherty failed to protect a child, tragedy happened,” a female narrator intoned over visuals of chains and crime-scene tape. Dougherty, supported by court papers, has said he has no recollection of ever receiving documents detailing the criminal history of the murder.

His denial is scorned in the ad. “No recollection?” the narrator said. “Tell Kevin Dougherty, ‘No more excuses. Keep our children safe.’ ”

Almeida said voters need to be informed but “negative ads are not a way to give voters accurate information.”

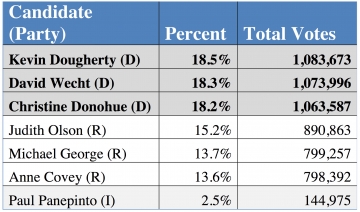

2015 Pennsylvania Supreme Court election results.

2015 Pennsylvania Supreme Court election results.Pennsylvania voters largely vote along party lines in low-information elections like the Supreme Court, said G. Terry Madonna, director of the Franklin & Marshall College Poll, the longest-running poll in Pennsylvania.

“The voter awareness identification of the appellate-court candidates as a whole is minimal,” he said.

Madonna used to survey Pennsylvanians’ awareness of Supreme Court candidates but eventually stopped trying. “There was literally no sense of awareness by the voters,” he said.

Almeida said that the order in which candidates are listed on the ballot can make a difference.

Candidates are grouped by party, and within each party’s list they appear in the order of the number of votes they received in the primary. However, in the primary, ballot order is determined by drawing numbers out of a coffee can.

“Because judicial elections are low-information elections,” Almeida said, “ballot position, name recognition, county affiliation are all real factors that impact who ultimately gets elected.”

As for name recognition, Madonna thinks David Wecht benefited from his last name. His father, Cyril Wecht, was a forensic pathologist who publicly disagreed with the Warren Commission’s finding that President John F. Kennedy’s assassination was the work of a single shooter. The father is well known in western Pennsylvania.

Similarly, Madonna said, Kevin Dougherty benefited from the vocal –and financial support – of his high-profile union leader brother. Dougherty led all candidates not just in votes but also in money raised.

Being from a populous geographic area can also help. Three of the candidates were from Allegheny County. Christine Donohue and David Wecht, both of Allegheny County, won two of the three open seats. (Max Baer, one of the sitting justices, is also from Allegheny County.) The third Allegheny County candidate, Judy Olson, finished first among Republicans and came in fourth overall. In an election where voters have much less motivation to vote than in a presidential election, Madonna said, just a bit of name recognition can make the difference.

Merit-selection supporters argue that an appointment system promotes diversity on the courts. The election of Christine Donohue means there will now be two women among the seven justices. However, on the state’s Superior Court, whose members also are also elected, women outnumber men, 10 to 8.

During the October debate in Harrisburg, panelist Arturo Varela, a senior reporter for Al Día, noted the lack of ethnic, racial and geographic diversity on the court. There are no ethnic or racial minorities on any of the three elected appellate courts, and after the election, three of the seven justices on the Supreme Court are from a single county, Allegheny. Also at the Harrisburg event, Paul Panepinto, the sole independent candidate, noted that all seven candidates in this year’s election were white. “There were two great African American judges who were in the process ... but they were not endorsed by the parties,” he said. Pennsylvania has not always elected judges.

The first state constitution in 1776 established seven-year terms for justices appointed by a twelve-member council. In 1790, a constitutional amendment gave the governor the power to appoint judges. In 1850, Pennsylvania adopted the practice of electing justices from a partisan ballot. In 1913, the elections were made nonpartisan but that was

reversed eight years later.

From the late 1960s onward, there have been many attempts to change to an appointive method of selecting judges. Former

Governor Robert P. Casey appointed a commission in 1988 to study the question, and

the so-called Beck Commission concluded that local trial court judges should be elected and appellate jurists appointed.

Over time, other commissions and groups – most notably Pennsylvanians for Modern Courts – issued reports making similar recommendations. However, the movement has never gained enough momentum to push the issue through the legislature. There, the winning argument has been that merit selection takes a right away from voters.

Taking decisions out of voters’ hands is never popular politically, said former state Senate President Pro Tempore Robert Jubelirer, who also served as the state’s lieutenant governor.

“Once, I got it through the Senate, but it died in the House,” Jubelirer said. “You always have members that say you’re taking the right away from the voters.”

Madonna added, “They want voters to decide – don’t take this important decision out of the hands of voters and into the hands of Harrisburg insiders.”

The last big push for merit selection was in 2001. Governor Tom Ridge, working with Pennsylvanians for Modern Courts, proposed a system for appointing Supreme Court justices. However, as the bill was being discussed, President George W. Bush asked Ridge to come to Washington after the attacks of Sept. 11. Ridge eventually became the first U.S. secretary of homeland security.

The legislation was abandoned, though Ridge was not finished.

In 2013, Ridge and three other former Pennsylvania governors announced their support for judicial reform. Democrats Ed Rendell and George Leader teamed up with Republicans Ridge and Dick Thornburgh to urge action by the legislature and the governor at the time, Republican Tom Corbett. Nothing happened on the issue.

In other states, scandals have often been the impetus for change. The first state to adopt merit selection was Missouri in 1940 after a corruption-filled election. Soon thereafter, Kansas went to an appointment system after a governor resigned so that the lieutenant governor could appoint him as chief justice. Oklahoma, Florida and Rhode Island also adopted merit selection after Supreme Court scandals. However, the push for merit selection has cooled off across the country.

It’s been 21 years since Rhode Island, the last state to make the switch, amended its constitution to enact merit selection.

In Pennsylvania on Oct. 20 of this year, the state House Judiciary Committee endorsed an amendment to the state constitution to appoint judges rather than elect them.

The proposal still needs to be acted on by the full House, but this is as far as merit selection has gotten in decades. This is the bill that would create a 13-person committee to create a list of potential judges, from which the governor would make nominations that then would be subject to approval by two-thirds of the Senate.

Proponents point to checks and balances in the bill. The recommending committee would be composed of lawyers and common citizens from both parties. Citizens would still have voting power, because judges would serve an initial four-year term and then stand for a yes-no retention vote for ensuing 10- year terms.

Of course, the bill must pass with a majority in both the Senate and House in two successive sessions and then be approved in a vote by the public. With Chief Justice Thomas G. Saylor just a year from mandatory retirement age and Senate Democrats calling for the resignation of Michael Eakin in the wake of the email scandal, it seems unlikely that this year’s Supreme Court election was Pennsylvania’s last.

Yet, proponents are optimistic. After the corruption that caused two vacancies this year and the record- breaking money spent on the politics of the Supreme Court race, they think the time is right.

“The stars may be aligning,” said Pat Christmas, senior policy analyst at Committee of Seventy, a Philadelphia election watchdog and judicial reform group. “There’s enough public disgust.”

(This story also appeared in The Lion's Roar on Dec. 1, 2015.)